Gurion came on May 15, 1948, and the ensuing war resulted in the expulsion or flight of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians Arabs from their land.(Before and after that, vicious pogroms in Arab countries also drove hundreds of thousands of Jews from their millennial homes, without compensation or right of return, but that’s another story.)

It is the first day of the working week for Israelis, and it may be disrupted by marches and demonstrations, some of which could turn violent. No one expects that exactly—although it has been rumored. With the Israeli Prime Minister in Washington begging Obama and the Congress to see things his way, it’s no time for Palestinians to give him backhanded support for his claim that they are not partners for peace. And with the recent pact between Fatah and Hamas and the approaching day in September when the UN General Assembly will likely vote to recognize a Palestinian state, local Arabs, whether citizens of Israel or residents of the occupied territories, don’t want to queer that process with a display of old-fashioned intifada-like violence.

Israel’s day of mourning began at sunset last Sunday, and we were witnesses to a solemn and stunning national ceremony at the Kotel—the Western Wall. It was also Mother’s Day in the States—Yom Ha’Em in Hebrew, I learned, although it’s not observed here—and I had gone out in the morning to buy flowers and I gift for Ann. Emek Refaim was bustling with the equivalent of what would be Monday morning business at home. When I walked into the flower shop, the radio was playing Yerushalayim Shel Zahav, Jerusalem of Gold, the song composed by Naomi Shemer just after the Six-Day War, and which has since become a kind of second national anthem, a sweet and melodic celebration of the results of that war—the ability to go freely to pray at the Western Wall, to live and build in the Old City and outside its walls, to drive down to the Dead Sea—Yam Hamelach or Salt Sea in Hebrew—for the first time in almost twenty years of statehood.

To the Israeli Left and of course to the Palestinians, the same song is a sappy, chauvinistic reminder of 1967 Jewish triumphalism, which, as the wisest predicted even then, would result in more than four decades of divisive occupation, Palestinian resistance, four more wars and two long violent rebellions, and growing worldwide opprobrium of Israel.

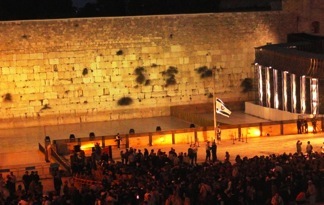

But Monday evening was not a time for politics. People crowded around us on the stone steps of the viewing area overlooking the Kotel. The wall was brightly lit with its ancient rough stone, tufts of dangling green plants that somehow survive in the crevices, and the unseen folded bits of paper by the thousands stuck into the spaces between the rocks every day. The plaza in front of the wall was cleared and then occupied by soldiers, sailors, and air force members in full dress uniforms snapping to full attention and shouldering arms sharply on command. A group of dignitaries marched in as the band played.

After the presentation of the colors, the flag was lowered to half mast and the speeches were delivered, including one by President Shimon Peres and one by Benny Gantz, the new Chief of Staff of the IDF—the Tzahal. I couldn’t understand much, but the words for fallen, remember, war, and State of Israel—Medinat Yisroel—were intoned over and over again, and the words for sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, husbands, wives, fathers,. mothers, and friends were comprehensible enough. So were phrases like all corners of the country, cities and villages, kibbutzim and moshavim, Druze, Bedouin, and Christian as well as Jews. Then Kaddish was said, as we stood and gave the responses as a congregation, and a chazan with a fine tenor voice sang El Molei Rachamim, God Full of Mercy, another traditional prayer for the dead.

After the ceremony ended we were part of a large crowd trying to leave, but police and soldiers blocked the exit until Peres and Gantz were well away from the Old City. We had experience a similar wait after President Obama spoke at the University of Michigan for two of our kids’ graduation ceremony last year. Eventually we heard helicopters and the soldiers pulled back gate into a street in the Old City, but not before some tension arose in the crowd, and two angry young men in separate incidents were arrested and quickly taken away for making trouble, or just for saying something provocative. That too is Israel.

Yesterday we were with friends in Jaffa for lunch—a march in advance of Nakba day was going on in the city and the police presence was impressive, but there was no violence. The guests included an intermarried couple—she Jewish, he Muslim, as is usually the case. Both were psychologists and had met when they taught in the same school thirty-seven years ago. Each had found acceptance with the other’s family in time, and with ten brothers and sisters his family produced a lot of acceptance—although their neighbors in Jaffa said hurtful things to and about her when she opened her home to them. Their daughters were taught about both religions but leaned Jewish.

The conversation turned, as it sooner or later does, to the conflict. She—let’s call her Michal—became tearful as she listed her losses: two cousins, five friends from high school, one from college. Her voice broke when she talked about the memorial day ceremonies all over the country where countless thousands gathered to mourn their dead in more than six decades of war. “Nothing has changed,” she said very sadly.

Last Sunday I had the big bouquet of lilies in my arms as I went into the bookstore to pick up the newspapers. “O, shoshanim!” the woman behind the counter exclaimed, melting at the sight of them. But these of course were not the lilies of the Song of Songs, or the lilies of the field in the Gospel. Those were much more modest, although still arrayed in splendor, The big, almost arrogant blooms of these cultivated lilies are close by me now, still gorgeous, still open to the morning.

Beautiful writing, as always, Mel.