This word, coming out of the mouth of Pope Benedict XVI, as he stood on the bima of the Park East Synagogue in Manhattan, brought back many memories.

Pesach—“ch” as in the Scottish “loch”—is the Jewish word for Passover, and it refers to the sacrificial lamb of the Exodus. The Hebrew slaves painted their doorposts with its blood, so God passed over (pasach) their homes while slaying the first-born Egyptians.

It is also “the paschal lamb,” which resonates rather differently for Christians; they think of the sacrifice of Jesus, the Lamb of God. Jesus, like the vast majority of Jews, attended Passover seders, and the Last Supper on the night before his death was one of them.

Was Pope Benedict thinking of this at Park East—a gorgeous architectural landmark I always make a point of walking past when I’m in New York–last Friday evening, a day before the first Seder? If so, he didn’t let on. “Dear friends, Shalom,” he began, speaking in soft, delicately German-tinted English, that of a gentle grandfather. Caught by my own fears and memories, I still heard the echoes of Hollywood-movie Nazis, and behind them Hitler’s hysterical screeching before vast, slavish crowds.

These resonances were not quite irrelevant. Benedict was born in Bavaria in 1927. Like all German boys, he joined the Hitler Youth, and was drafted at age 16 into the anti-aircraft corps as the war drew to a close. He shunned Hitler Youth meetings—a cousin of his with Down syndrome was murdered by the Nazis—and eventually deserted, but had to spend several months in an allied prisoner-of-war camp.

It’s not a record of heroic resistance, to be sure, but few of us can know what we would have done. More than sixty years later, he stood in a modern Orthodox synagogue in New York and gave the rabbi—an Austrian-born Holocaust survivor—a medieval Hebrew manuscript by a famous scholar, and received in return a silver Seder plate and a package of matzoh, which he said he would eat on Passover.

“It is with great joy that I come here, just a few hours before the celebration of your Pesach," the Pope said. And the rabbi said, “I thank God that both of us survived.”

The rabbi’s survival at least was no thanks to the Catholic Church, which stood by while six million Jews were murdered. For two millennia the Church viciously persecuted the Jews. Pope after Pope incited murder, forced conversions, ordered inquisition and torture.

But this is a new day. I was eighteen in 1965, at the time of the Second Vatican Council, which issued the edict Nostra Aetate—Our Time:

“True, the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still, what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today…the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God…Furthermore, in her rejection of every persecution against any man, the Church, mindful of the patrimony she shares with the Jews and moved not by political reasons but by the Gospel's spiritual love, decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.”

This was a formal reversal of two thousand years of replacement theology: The killing of the Lamb of God would no longer be blamed on the Jews; more strongly, “the Church, mindful of the patrimony she shares with the Jews” signaled a new era of respect.

Benedict’s predecessor, John Paul II, became the first Pope to set foot in any Jewish house of worship when he visited Rome’s central synagogue in 1986. Jews had been there, on the banks of the Tiber, longer than Christianity had, but this was the first Pontiff who crossed town to say hello. And he said a lot more than that.

In the language of Nostra Aetate, he condemned anti-Jewish acts “at any time, by any one.” And in case you missed it: “I repeat: ‘By anyone.’”

He also went further: “The Jews are beloved of God, who has called them with an irrevocable calling…The Jewish religion is not 'extrinsic' to us, but in a certain way is 'intrinsic' to our own religion…With Judaism, therefore, we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion. You are our dearly beloved brothers, and, in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.'' This was not just absolution–it was a new theology.

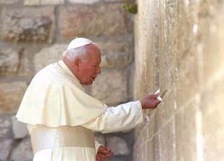

between the stones. His read: "God of our fathers, you chose Abraham and his descendants to bring your name to the nations. We are deeply saddened by the behavior of those who, in the course of history, have caused these children of yours to suffer."

He also visited Christian sites, and the next year I stood in the place overlooking the Kinneret—he would call it the Sea of Galilee—where thousands heard his sermon and where, by tradition, Jesus delivered the Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.”

Pope Benedict is among them. We needn’t delude ourselves that this is a straight path. Recently the same Pope seemed to lead his church away from it, reviving a prayer that calls for the conversion of the Jews. But his words at a historic synagogue in New York seek reconciliation, and suggest that his heart was softened, not hardened, in this Passover season. Jews, and others too, can be thankful that we live in our time.